|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Независимые часовщикиФорум о независимых швейцарских часовщиках. |

|

|

|

|

Опции темы |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Независимые часовщикиФорум о независимых швейцарских часовщиках. |

|

| Ссылки сообщества |

| Социальные группы |

| Цитаты Watch.ru |

| Галерея фотографий |

| Галерея фотоальбомов |

| Конкурсы и викторины |

| К странице... |

|

|

|

Опции темы |

|

#1

|

||||

|

||||

|

An Insider's Look at F.P. Journe

На WatchTime выложили материалы о FPJ в нескольких частях. Хотя материал "проспонсирован" (читай - рекламный), там есть кое-что интересное про модели мастера...

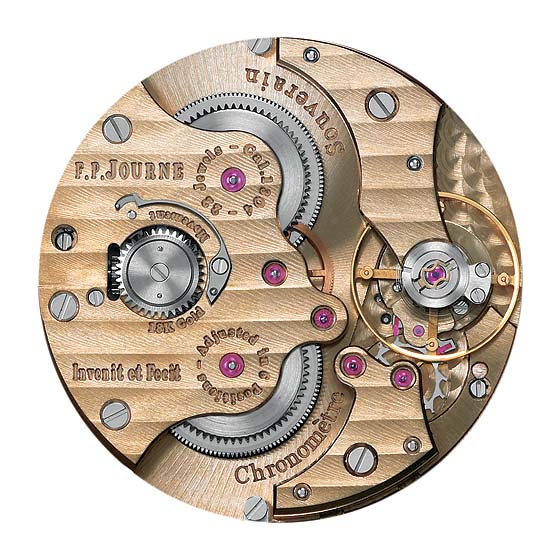

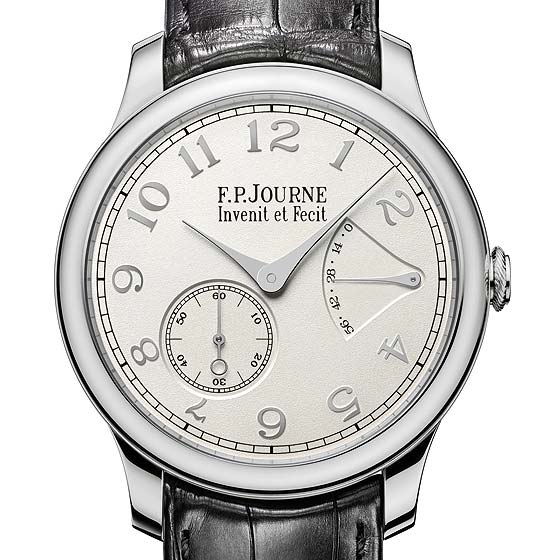

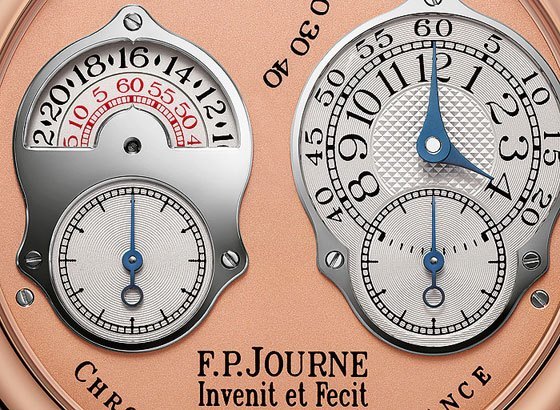

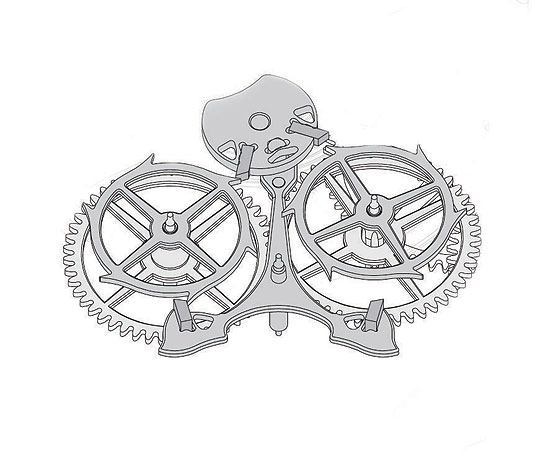

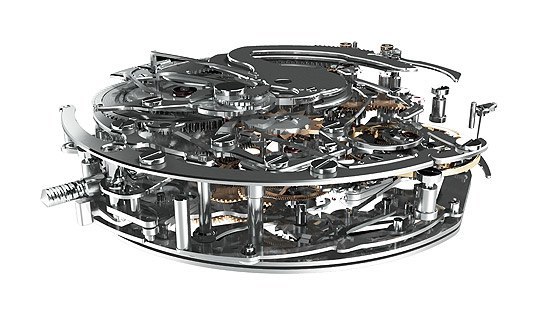

Он выложен в пяти частях. Так что и сюда помещу в том же формате ))) Power or Precision? An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe (Part 1) Ten years ago, when F.P. Journe introduced his Chronomètre Souverain, his goal was to achieve a true Chronometer status. Precision has always been the essence of Mr. Journe’s quest. His two first attempts were the Remontoir d’Egalité that regulates the flow of energy in his Tourbillon, and the Resonance movement that compensates for the movement of one’s wrist (making it — de facto — the only true wristwatch in the world). For a “seemingly” simple timepiece, Mr. Journe elected to fit his Chronomètre Souverain with a double barrel. But unlike his peers, the goal was not to achieve a longer power reserve. By fitting each barrel with a very long (1 meter long) but loose spring, Mr. Journe flattened the power curve. To easily understand the concept, imagine a spring when it is fully loaded. It has a “speeding” effect on the movement and as it dies, power gets weaker and therefore the timepiece has a tendency to go slower.  Now, any watchmaker can make a chronometer where the average over the power reserve is close to zero. But who is looking for average when telling time? When one looks at his timepiece, one should be able to tell the exact time (and not the average over a certain period of time). To illustrate this system, Mr. Journe decided to emphasize each of the main components by seemingly disconnecting them.  One other specification that Mr. Journe set was that the thickness of the movement was not to exceed 4 mm. In order to achieve this, he had to overcome one major problem. The power-reserve indicator system that he was using at the time was 1.57 mm thick and therefore not adequate. He had to create (and then patent) an ultra-slim power-reserve indicator using ceramic ball bearings. It shrunk to 0.5 mm and became the system used in all FP Journe timepieces thereafter. To mark the Chronomètre Souverain’s 10th anniversary, F.P. Journe launched a new series of dials. Here, again, apparent simplicity was not easy to achieve. Working closely with his own dial-making atelier, Mr. Journe and his technicians were able to make the new dials from a solid gold coin. The dial gets stamped on all sides and surfaces, except for the numbers that are thus raised. The normal technique would have been to apply those numbers, but numbers like the “7” are too small to use that technique. After many different trials and much time, the new Chronomètre Souverain was born.  This dial execution (available also with red gold numerals on the red gold Chronomètre Souverain) was almost as difficult to achieve as the dial of the famous Chronomètre Bleu. The issue with “simple” dials is that the minutest blemish is magnified. To this day, the Chronomètre Bleu dial has close to a 65% rejection rate by Mr. Journe’s quality control team. Interesting, and so like Journe, to give his least expensive timepiece the most difficult dial. But Mr. Journe’s goal is not to achieve quantity (the company still produces between 800 to 900 timepieces a year). His goal is to express his artistic and watchmaking wizardry through his timepieces. This is also the reason why all F.P. Journe timepieces come with 18k solid gold movements (except the Sport collection, with its never-before-seen aluminum movements). But as Thomas Edison first said: “Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.” F.P. Journe is the only company in Switzerland in which the founder is also the president AND the watchmaker. And where may you find Mr. Journe in is manufacture? At his bench, day in and day out.  Сама ссылка: http://www.watchtime.com/advertiseme...-journe-part-1 Who Needs Constant Force? An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe (Part 2) 1977. Paris. A young watchmaker of 20 embarks on an odd quest – to make his own tourbillon. Not to sell, not to show, but simply to prove that he can do it. Passionate and determined, equipped only with George Daniels’ book, “the Art of Breguet,” Francois-Paul Journe sets to work.  1983. Paris. Francois-Paul Journe completes his first watch:  Francois-Paul Journe’s first ever watch. Started in 1977, finished in 1983. Now part of the F.P. Journe museum collection. It took more than five years to conceive and create a pocketwatch that was never meant to be sold – and not just a simple watch, but a tourbillon. In the ’70’s and ’80s tourbillons were not the craze they are now. Only George Daniels (and then Journe) created a new, modern tourbillon. Forward to 1984. Still trying to master the tourbillon (and especially the pernicious effects it has on accuracy); François-Paul makes his first Remontoir d’Egalité in his second and fourth (pocket)watch. It caught the attention of a major collector, Eugen Gschwind (Google the name or visit his collection at the Historiches Museum Basel).  Francois Paul Journe 4th watch (1984). Fast-forward now to 1991. Francois-Paul Journe creates his first wristwatch – a tourbillon, of course, but also fitted with a remontoir d’égalité, or constant force. This sort of device became popular a few years ago (thanks in part to great articles such as Alan Downing’s, followed by David Chokron’s in-depth writings in Watch Around No.15, Spring-Summer 2013, pp 44-53). As one may recall in“Power or precision? An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe – Part 1”), due to the nature of the spring, any mechanical object will have more power when the spring is fully loaded, and inversely less as it unwinds. A constant force system is “simply” a system that allows regulating the delivery of energy to the balance wheel. It is not a new issue. Watch masters such as Breguet, Lepine, Berthoud, etc. already had that issue in mind. But in 1991, very few people understood it, or cared.  Francois Paul Journe’s first ever wristwatch (1991). Now part of the F.P. Journe museum collection. What makes F.P. Journe’s patented device superior to its new competitors’ is the simplicity and the lightness of his device. The heavier the device, the more power needed to move it and the more friction it creates (like a “fusée à chaine,” which was a good idea in the 18th century but too heavy to be efficient today). The solution becomes counterproductive to the outcome. Because the remontoir d’égalité delivers the same packet of energy to each and every second, the seconds hand actually moves and dies every second. Thus it is called a dead second. Like a quartz movement, the second hand does not sweep. Note (and this is important to Mr. Journe) that it is a natural dead second, meaning that unlike some of his competitors, his goal is not to make a dead second mechanism (what would be the point?). It is simply a natural by-product of the remontoir.  Tourbillon Souverain with Remontoir D’Egalité avec Seconde Morte (Dead Second). Часть третья... Is Your Wristwatch a “Wrist” Watch? An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe (Part 3) From 1910 to 1920, the Swiss industry had hunches on where the market for timekeepers would lead them: pocketwatches or the new craze, wristwatches. In what we call the “conversion era,” Swiss watchmakers basically rotated their pocketwatches by 90 degrees, added lugs and voilà: here was your wristwatch. But by doing so, watches were now confronted with a new issue: the movement of the wrist. As you move your wrist, due to centrifugal (or inversely centripetal) forces, balance wheels have a tendency to go faster (more precisely, have a larger amplitudes) or inversely, thus affecting the accuracy of the watch.  Resonance Movement As usual with François-Paul Journe, this idea had been on his mind for some time. As far back as 1984, he attempted to confront the issue with his first resonance watch.  Francois-Paul Journe resonance movement in his third watch (1984) Journe attempted to include this system in a wristwatch, inspired by his masters (in this case, Antide Janvier and Abraham Louis Breguet, who made six pendulum clocks using the resonance phenomenon. One Janvier clock is in Mr. Journe’s office; another one is at the Patek Philippe Museum). What is resonance? It is an acoustic principle: put a watch to your ear and you hear a “tick tock.” Energy has been released in an acoustic form. It makes the air vibrate until your ear membrane absorbs it and gives your brain the information. There is an emitter (the watch movement) and a receiver (your ear). So the “tick-tock” is proof of energy being released but not used. In the F.P. Journe Chronomètre à Résonance, you have a double movement with two balance wheels that are both emitters and receivers. It is a law of physics that when two sources produce energy, if they are on the same frequency, they will communicate. Each “talks” and each “listens.” And nature makes it so that they balance each other in opposition. In real life, what happens? If a truck passes nearby creating a lot of noise, or if there is a shock, the vibration will modify the balance of the escapement. As the energy received by both balance wheels are in opposition, one will go faster, one slower. As they “resonate” they will balance each other, therefore nullifying the shock/perturbation. To quote Jack Forster in his article, “In Plain Sight: Revealing The Secrets Of F.P. Journe’s Chronomètre à Résonance” (2014): “the Résonance is constructed along exactly these principles [those explained in George Daniels’ book: The Art of Breguet, p. 76]. The balances are free-sprung (with no regulator) and regulation is through the use of weights to vary the inertia of the balances. As with Breguet’s resonance pocketwatches, the adjustable masses used for regulation are inside the rim of the balance (in the case of Journe’s watches, on the arms). Breguet’s notes on pendulum clocks are detailed and he notes that the two oscillators have to be closely regulated to each other for a resonance effect to occur.” How close? If you pay attention to the movement on the left, you have a screw that can be adjusted to bring closer (or make further apart) the two balance wheels. Note also that with all F.P. Journe watches the balance wheels have the weights on the outside for ergonomic reasons, but in the case of the Résonance, there was no other way.  Also, when one moves one’s wrist, one balance wheel will go faster while the other one will go slower. As they “resonate,” they will readjust themselves and therefore compensate for the movement — making the Résonance the only “true” wristwatch. As Lavoisier said: “In nature nothing is created, nothing is lost, everything changes.” Proof? As Anthony G. Randall explains in his article, “Anthony G. Randall discusses F.P. Journe’s Chronomètre à Resonance” (F.P. Journe’s Chronometre a Resonance ) “a remarkable demonstration of resonance being achieved [is by] using a Witschi timing machine. This machine is able to produce a diagram of the sound of the lever escapement. With two escapements working simultaneously, but not exactly in phase initially, two similar diagrams appear close together. Gradually, as resonance occurs, the two diagrams merge into one. The combined rate then appears as a straight line.” For those in doubt, please see this experiment of synchronizing 32 metronomes at Resonance and Communications. The seconds hands (as seen below) will always show the same position.  Dial of the Résonance Because there is a double movement, it allows the user to set two different times on each of the dials. There is much debate on what makes a watch a true world timer. Obviously the resonance offers much more than a GMT (which only partitions time in one-hour increments over 24 hours). But many countries never adhered to the 1884 Washington International Meridian conference. Countries such as Australia use a half-hour increment. Nepal is UTC +5:45! Here you may set two different times that are totally independent — except that their seconds will be in sync.  Сама статья: http://www.watchtime.com/advertiseme...-journe-part-3 ------- ДОБАВЛЕНО ЧЕРЕЗ 26 МИН -------- Продолжаем, часть 4 How to Make a Perfect Watch: An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe, Part 4 Every watchmaker interested in precision has to deal with the same four major issues. If all four of these issues could be resolved, one would obtain the perfect watch. But like the Perpetual Movement or the Fountain of Youth, this quest for the Holy Grail is not achievable in our lifetime. But this does not mean that we should not attempt to get closer to it. Attaining that perfection is Francois-Paul Journe’s obsession, and what makes him return to his workbench day in and day out. The issues in question are plainly illustrated in the conception and making of the F.P. Journe Chronomètre Optimum. (Note: there is a reason that it is called the “optimum” – Journe is a man of few but highly selective words). The Chronomètre Optimum symbolizes the very essence of precision for a wristwatch. It is probably the most complicated three-handed (four-handed if you count the power-reserve indicator) watch ever.  Chronomètre Optimum movement It addresses the aforementioned four major issues of a mechanical watch’s precision: 1. The linear delivery of power. Like the Chronomètre Souverain (see “Power or Precision? An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe, Part 1”), the Chronomètre Optimum has two barrels to insure the stability of the driving force. 2. The regulating of power delivery. The Chronomètre Optimum is outfitted with a Remontoir d’Egalité (constant-force remontoire, Patent EP1528443.A1; see “Who Needs Constant Force? An Insider’s look at F.P. Journe, Part 2”). Additionally, for the first time, the Remontoir is made of titanium for greater efficiency due to its lightness. As we have seen in the past few years, many watch companies are introducing constant-force devices. Be wary of their marketing claims. If the system to regulate the delivery of power is too heavy, it creates too much friction and thus makes it counterproductive. The heavier it is, the more power it needs to counteract the added friction, creating an unsolvable cycle. This is why Journe’s is super light.  3. The issue with lubricants. This is 2015, not 1801! Whereas Abraham-Louis Breguet was constantly struggling to find the best lubricants of his time (including animal grease and even fish oil), today’s synthetic lubricants offer a great longevity and are immune to drastic changes in temperature. There are two main parts that need to be lubricated in a timepiece: the pivots of the gear train and the regulating organs. At 21,600 vph, the lubricants used for the regulating organs are going over more than four years before drying up, therefore creating more friction and leading to a loss of amplitude, thus losing in accuracy. This is usually the time to have your timepiece serviced. So the problem becomes the deterioration of lubricants, not the use of them! One way to deal with this issue is to avoid using lubricants altogether. Journe says, “The use of silicium is the wrong answer to the right question.” Silicium (silicon) creates virtually no friction and hence does not need lubricants. But silicium is extremely fragile, and would need to be replaced at each overhaul. This is as long as it is available. If not, there will be no way to replace that part, and the movement will end up in the garbage. “My watchmaking philosophy is to make watches that will still work in 200 years,” Journe says. “Those made 200 years ago are still in working order today if they have been maintained regularly. It is for this reason that I only use solid materials that have proven their worth rather than modern materials that will probably be unable to be repaired in a few decades.” By patenting a brand new escapement system (the EBHP High-Performance Bi-axial Escapement), Journe was able to avoid the use of lubricants. EBHP is the only direct impulse escapement to start up on its own. And not only does it function without lubricants, it also has a far greater output than do the majority of escapements: 50 hours without loss of amplitude. Many dual-wheel escapements have been created in the past, the most efficient being A-L Breguet’s “natural” escapement.  4. The “heartbeat” of a movement. The Chronometre Optimum is fitted with a spiral with Phillips curve, insuring better equilibrium. The two different second hands show the two different outputs of the mechanism. One from the escapement and the other from the Remontoir d’Egalité. Variations in some of the watches from the Souveraine collection: – The Chronomètre à Résonance achieves a constant rate when it is exposed to the movement of the wrist. This watch is very accurate because its rate is not affected when the watch is worn. – The Tourbillon Souverain: the classic tourbillon is not generally an ideal watch in terms of accuracy, but combined with a constant force remontoire, its stability is guaranteed. – The Chronomètre Souverain: has the same accuracy as the Chronomètre à Résonance but does not cancel out the effects of a moving wrist. With these four issues addressed, Journe was able to test the watch in two ways. The obvious test was to add lubricants to the bi-axial escapement to see if the watch would function better. It did not. The second was to test the amplitude which continued to have a far greater output than the majority of escapements: 50 hours! Francois-Paul Journe is far from claiming that he has found the Holy Grail. But the quest for it is a reward in itself. If, one day, you happen to visit the F.P. Journe Manufacture in Switzerland and ask to see where the boss works, you will be taken not to an office, but to his watchmaker’s workbench.  F.P. Journe Chronomètre Optimum

|

||||

|

|

#2

|

||||

|

||||

|

Последняя (на данный момент) часть...

Sound and Vision: An Insider’s Look at F.P. Journe, Part 5 Grande Sonnerie [Def]: a watch that strikes the hours and quarters automatically. The Professional Dictionary of Horology is clear about the function of a Grande Sonnerie. But let’s understand what it means by “automatically.” Here it does not refer to an automatic movement, but rather that, without outside help, the watch will strike, on its own, in passing, every hour, and repeat the hours and indicate the quarters at each quarter. (Note that in Petite Sonnerie mode, it will strike the hours on the hour and only the quarter on the quarter, similarly to a grandfather clock.)  Grande Sonnerie Souveraine movement When François-Paul Journe embarked on what he later called the “climbing of Mount Everest,” there was no modern Grande Sonnerie in the market. Most of the offerings were old pocketwatch movements mounted in wristwatches. His specifications were set in stone from the get-go. Not only would his creation follow the exact definition of a Grande Sonnerie, but it had to have a long power reserve and be able to be used by a 10-year-old child. A mere six years and 10 patents later(!), the F.P. Journe Grande Sonnerie Souveraine was born, and won the Golden Hand at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie of Geneva in 2006. What makes this watch so revered and complicated?  Mode selector: “G” for Grande Sonnerie, “P” for Petite Sonnerie and “S” for silence Friction and power issues (as in all mechanical watches) are exacerbated in the Grande Sonnerie. Consider friction: the Grand Sonnerie chimes 96 times per day; the hammers strike 912 times per day or 332,880 times per year. Which brings another problem to the plate: wear and tear! Just imagine hitting a table with a little hammer that many times. It would destroy the table. As for the issue of power, the “easiest” way to circumvent this extraordinary thirst of energy would be to add a few mainsprings or to have a short power reserve. Journe did none of that. He created (and patented) a unique mainspring mechanism that feeds the timekeeping functions on one side and the chiming ones — independently — on the other. Thus, timekeeping has a power reserve of five days. When it is in Grande Sonnerie mode, the Sonnerie will work for 24 hours, after which a (patented) system blocks the chiming mechanism, leaving still 24 hours of timekeeping. If the watch does not chime, it is time to wind it. The other issue is the protracted fragility of Sonneries. The F.P. Journe Sonnerie Souveraine features patented security systems that keep the watch from striking when the winding crown is pulled out, and that ensure that the winding crown may not be pulled out during striking. It is somewhat similar to a perpetual calendar that would prevent you from setting between certain hours (as the gears are engaged). This results in total security, and ensures for the first time that the mechanism cannot be damaged by incorrect manipulation — therefore making it the only striking watch that is completely safe to use.  The Grande Sonnerie –like every chiming watch from Journe (i.e., the Minute Repeater) is in steel. Steel has a crystalline formation, as opposed to platinum and titanium, which are made from an aggregate of powder. Sound has two components — volume and quality — and steel offered the best compromise. Sound and vision? Why do Grande Sonneries (and minute repeaters) delight the watch collector so much? One clear answer is that their level of complication is unmatched. It seems a bold concept — hearing the time versus seeing it — but this is not actually new. Actually, time was heard rather than seen for centuries. When time began to be communicated in the 14th and 15th centuries in Europe (Northern Italy, France and Germany, mostly), the clocks in churches did not have dials. After all, who would see them? Certainly not the farmers, who could be miles away. So, monks or priests hit on bells to indicate time to those far away. Proof? When we say 4 o’clock, we refer to “4 of the clock,” which, in the late 14th century, meant bells (clock comes from the Old French cloke; Modern French is cloche for “bell”). Thus, 4 o’clock means literally “4 of the bell.” More proof? The origin of the word “noon” comes from the nona prayers. Nona used to refer to the ninth hour of sunlight, but in the mid-12th century, church prayers shifted from ninth hour to sixth hour, or roughly midday. Once again we referred to sound – hearing the nona prayers, one knew it was 12 noon. The Grande Sonnerie is a testament of F.P. Journe’s vision: do one complication per movement but do it as well as you can and do it while limiting the number of parts (so as not to create more friction or problems). This movement has “only” 408 parts and an overall diameter of 35.8 mm. To quote Antoine de St Exupéry from “Night Flight”: “A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”  Grande Sonnerie with typical offset dial and hammers visible on the left Сама ссылка: http://www.watchtime.com/advertiseme...journe-part-5/

|

||||

|

| Эти 3 пользователей сказали Спасибо! serg70 за это сообщение: | ||

|

#3

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Похожие темы

Похожие темы

|

||||

| Тема | Автор | Раздел | Ответов | Последнее сообщение |

| Pilot collection 2013 и заметки о заводе в Le Locle (от watch-insider.com) | Krisz | Zenith | 0 | 21.01.2013 19:59 |

|

© 1998–2024 Watch.ru

По вопросам рекламы

|